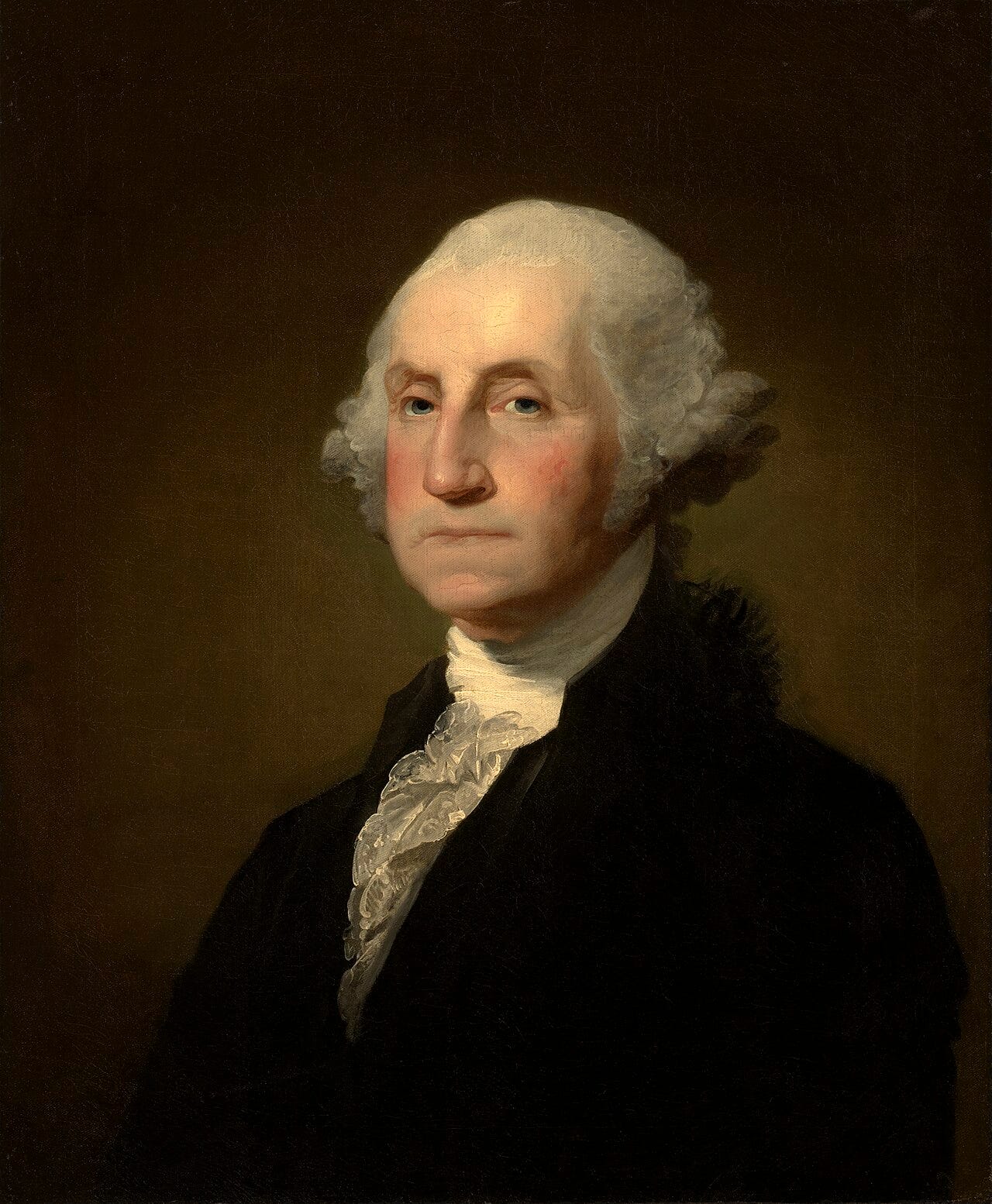

In 1796, George Washington, the first president of the United States, decided to retire from public life at the age of 64. He’d serve out his second term until its completion the following year, and being his political life to a close. But before he did that, he chose to pen a farewell address, warning Americans about the greatest danger they faced.

In my mind, throughout American history, there are two great farewell addresses by presidents sounding the alarm about insidious threats to the welfare of the nation. President Eisenhower’s farewell address in 1961 was shocking because, despite being composed in the midst of the Cold War, it didn’t argue that the greatest menace to American life was communism, which would have been the obvious choice. Rather, he railed against the peril posed by the military-industrial complex. But just as important and just as surprising was Washington’s farewell address. In it, Washington laid out his case that the number one enemy to the stability of the nation was political factionalism. Going even further, he hinted that the very existence of rival political parties was a recipe for disaster.

Considering that Washington’s words seem more applicable than ever, let’s unpack them.

Let’s start with a few selections from the farewell address.

“However [political parties] may now and then answer popular ends, they are likely, in the course of time and things, to become potent engines by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people and to usurp for themselves the reins of government, destroying afterwards the very engines which have lifted them to unjust dominion.”

“I have already intimated to you the danger of parties in the state... Let me now take a more comprehensive view and warn you in the most solemn manner against the baneful effects of the spirit of party, generally. This spirit, unfortunately, is inseparable from our nature, having its root in the strongest passions of the human mind… The alternate domination of one faction over another, sharpened by the spirit of revenge natural to party dissension, which in different ages and countries has perpetrated the most horrid enormities, is itself a frightful despotism. But this leads at length to a more formal and permanent despotism. The disorders and miseries which result gradually incline the minds of men to seek security and repose in the absolute power of an individual; and sooner or later the chief of some prevailing faction, more able or more fortunate than his competitors, turns this disposition to the purposes of his own elevation on the ruins of public liberty. Without looking forward to an extremity of this kind (which nevertheless ought not to be entirely out of sight) the common and continual mischiefs of the spirit of party are sufficient to make it the interest and the duty of a wise people to discourage and restrain it. It serves always to distract the public councils and enfeeble the public administration. It agitates the community with ill-founded jealousies and false alarms, kindles the animosity of one part against another, foments occasionally riot and insurrection. It opens the door to foreign influence and corruption, which find a facilitated access to the government itself through the channels of party passions. Thus the policy and the will of one country are subjected to the policy and will of another.”

And in another passage, he speaks of ‘external enemies’ who ‘covertly and insidiously’ will undermine national unity for their benefit, and he advises Americans about “indignantly frowning upon the first dawning of every attempt to alienate any portion of our country from the rest, or to enfeeble the sacred ties which now link together the various parts… One of the expedients of party to acquire influence within particular districts is to misrepresent the opinions and aims of other districts. You cannot shield yourselves too much against the jealousies and heart burnings which spring from these misrepresentations. They tend to render alien to each other those who ought to be bound together by fraternal affection…”

What exactly is Washington telling us in these passages? What is the problem with having political parties? To put it simply, parties encourage factionalism. Theoretically, politics could consist of fellow citizens working together to solve problems. Obviously, not everyone would agree about the steps necessary to solve such problems, but it’s far from impossible to find compromises about strategy. What can’t be compromised, instead, is party allegiance masquerading as strategy. Factionalism leads to a place where solving practical problems doesn’t really matter, since factions primarily care about scoring a point for their team. Politics and effectively running a government stop being cooperative efforts and turn into gang fights to outdo your ‘enemies’ and score victories for your side. Loyalty is no longer to the nation or to what’s right, but shifts entirely to one’s group. The end scenario is where we are today: someone could find a cure to every disease known to mankind and create world peace, and they’d still be opposed by political rivals since those solutions didn’t come from their party.

If this is not stupid enough, what’s even more ridiculous about factionalism is that it’s a game no one can win long-term. Even if your political team is getting everything it wants at some point, it’s a guarantee that eventually the wheel will turn, someone else will be in power and they’ll reverse everything your side fought for.

Worse yet, political parties and factional politics offer a fantastic excuse to distract people from the real power plays being made behind closed doors. Divide and conquer is the oldest game in the book. Case in point: if I were a slave owner back in the early 1700s, and I owned both black slaves and white indentured servants, I’d have a problem. All of them would be much too aware that I’m the one exploiting them. But if instead I could give slight preferential treatment to one group, foster jealousies among them, and get them to be at odds with one another, now my job would be infinitely easier since they’d be too focused on arguing with each other to remember that I am their common enemy. Political parties offer a similar chance at staging a theater of distraction: get voters to argue about which side is best, when all of them are committed to an existing status quo and none of them truly have the voters’ best interests at heart.

Of course, our situation today is much worse than anything Washington could have envisioned. Not only are we dealing with the ever-present defects of the human mind, its obsessive desire to belong to an in-group, and the sleights of hand performed by power players, but we also have to contend with social media algorithms profiting from creating maximum division. Professional merchants of outrage build careers fanning the flames of factional politics, free to monetize on what they know will make them rich. Their game is simple: pump out anger, hatred, find suitable scapegoats, demonize some other side, collect a check, rinse and repeat. We are bombarded 24/7 by factionalism on steroids while the monsters are laughing all the way to the bank, and real problems remain unsolved.

Washington was right. I have no doubts about it. The question is what can we do about it, since this is a battle that the modern world in general, and the United States in specific, is badly losing. Good, ole Bob Marley once wrote,

“If you get down and you quarrel everyday,

You’re saying prayers to the devils, I say.”

Perhaps, our individual effort not to fan the flames doesn’t change things on a larger scale. But perhaps it’s not a bad place to start.